Unraveling the Secrets of the Self Through ‘English’

I feel different when I speak English.

In middle school, we had a “wai jiao”, a foreign guest teacher who’d come hang out with us a few times a year: Canadian Stephen (he pronounced it steh-fun) had dirty blond hair and frequent stomach problems. Stephen described English as “simple, and elegant.”

For me, it was the language of Sherlock Holmes, of Julie Andrews from The Sound of Music (even though later I’d find out they’re all supposed to be Austrian), of Humphrey Bogart saying “here’s looking at you kid,” of Hamlet and his everlasting “to be, or not to be”… precise, direct, logical, following strict sets of rules, which was very different from the paradoxical Chinese, where one must pluck out meaning from chaos, and a singular character could mean multitudes. English was a language that I fell in love with, gradually, increasingly, a language that I’ve been tested on more times than I could count until eventually I dared list it as one of my “primary languages.”

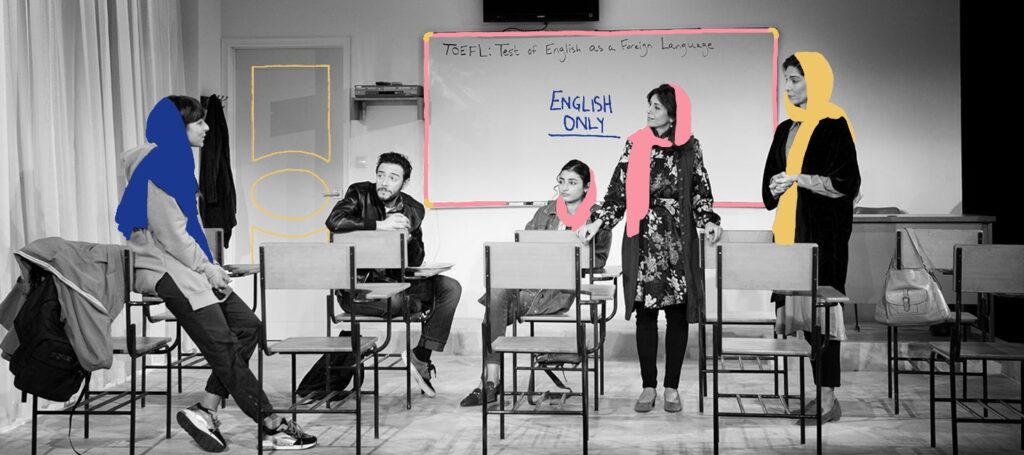

One of those tests was the TOEFL: Test of English as a Foreign Language, the golden fleece at the center of Sanaz Toossi’s English. The teacher, Marjan (a poignantly nuanced portrayal by Marjan Neshat), spells it out for us on the whiteboard, and then in massive font writes and underlines “ENGLISH ONLY.”

Over the course of the play, under Knud Adams’ careful direction, English reveals itself to be an exquisitely crafted production. You get to know a quintet of characters, each complex in different ways, with practically nothing in common save for their shared goal of passing the TOEFL. You observe their interactions from all angles, both metaphorically and literally: Marsha Ginsberg’s understated yet effective set spins on a turntable, which allowed the sterile test-prep classroom to be on display from various points of view, and propelled the narrative forward in a dynamic way. This is also enhanced by Reza Behjat’s liquid-seamless lighting and Sinan Refik Zafar’s auditory transitions.

My experience at English was a nostalgic, enlightening, and somewhat shattering one. Having sat in an almost identical classroom – all right angles and cold tones – for months on end, working towards a quantifiable goal. The play resonated with me beyond its cultural specificity (as it speaks from a 100% Iranian experience) and I believe it will do the same for anyone who’s gone through the process of learning English as a foreign language with a hope for a better future: an idea symbolized by a test score that’s just as simple and elegant as the language it evaluates (thank you, Canadian Stephen).

In the opening scene, 18-year-old Goli (an infectiously bright-eyed Ava Lalezarzadeh) speaks of the language with fondness, in heavily accented English, per Marjan’s classroom rule – “ENGLISH ONLY”, which is frequently and strictly reinforced. This is also where the play sets up a convention to differentiate the spoken languages, for although it’s performed almost entirely in English, the play featured characters who communicated (struggled with accents) in English as well as Farsi (with more eloquence, nuances, and without accents). Even though the shifts between different modes of communication remain subtle, the clarity is rarely lost, “English does not want to be poetry like Farsi,” we learn.

The play drops us into this world quickly but takes its time to unfold the layers of its characters, albeit with calculated ease: you discover the depth and poetic streak behind Goli’s girlish naïveté, and can’t help but imagine a future for her with infinite possibilities. You feel the indomitable undercurrent within Roja’s steely poise – Pooya Mohseni made me teary with her portrayal of an Iranian mama (not mom) with a quiet yet unyielding pride in her own language and culture.

You also realize the hidden vulnerability and inner conflict of Elham (a commanding Tala Ashe), which she masks through fierce competitiveness, only to suddenly have all her sharp edges soften making you root for her. Then there’s the teacher’s pet Omid (Hadi Tabbal) who speaks near-perfect English and probably doesn’t need this class. You know there’s something fishy about him, but Tabbal makes him so insufferably likable that you just go with it.

The characters learn English through show-and-tell, forced and meaningless conversations, role-play, word games, and songs – Goli shares a Shakira number in earnest (“Baby, I would climb the Andes solely to count the freckles on your body”). I remember being confused by it as much as Goli, because that’s how I learned English as well: through dictating everything from Tom Dooley to Harry Potter, through dubbing scenes from Mean Girls, reading Edith Wharton with a dictionary, watching entire seasons of Sex and the City at 16 before sex was a remotely tangible concept.

It takes years of toil and trouble for you to finally make people laugh in a language that’s not even your own. You take pride in that as if you’ve somehow gained a superpower or been granted access to a big secret – except it’s not enough, it’s never enough.

As foreigners, we try to be accommodating, to ingratiate ourselves into a society because we’ve been inundated with the idea of being inferior for lack of a language – so we’re willing to forgo our own sense of identity, our names – I think about the fact that we chose English names in class because somehow that’s more “proper”; I think about the fact that I pronounce “Shanghai” in an American accent, and never protest when people who have known me for years mispronounce my name. “Our mothers get to name us,” Roja’s words echo, quiet, yet resolute, “Not foreigners.”

When does a place become a home, I wonder? Having lived in the US for over a decade, speaking English with barely an accent, I still have trouble thinking of it as “home.” How do you feel “at home” in a country that you’ve spent years of your life assimilating to its culture, learning its language, while it propagates xenophobic rhetoric against the place you’re from? “Do you ever think about who you would be if you never had to think about staying or leaving?” Omid laments, a son of both worlds, uncertain of where he truly belongs, and yet, for many more, thinking about staying or leaving as a choice at all, would be a luxury.

In a moment of honesty, Marjan claims: “I always liked myself better in English.” For a time, I felt exactly the same. I got to reinvent myself in English: I was more candid, outgoing, more self-assured…I was simply louder. Marjan’s journey, or rather, her unraveling, made me well up, because I saw her as Charon the ferryman, ushering each passing soul into the next version of their existence, while she remains stranded between different shores.

During a crucial moment, Marjan speaks in Farsi to Goli, revealing a vulnerability reserved only for her mother tongue, a language that’s connected to her ancestry, to a land that accepts her no matter what – and it’s something no native English speaker can ever claim to relate to, not completely.

I am different when I speak English. I’m more sophisticated, more confident, because I have to, because there’s always something to prove, in a country that takes you in with indifference at best, and at times, with hostility or contempt.

So after all that, did I like English? How do you, indeed, simply “like” something that conjures up a part of you that you take so much pride in, yet simultaneously feel utterly ashamed of? What I do know for sure is this: Sanaz Toossi has given a gift to native English speakers and foreigners alike, through which, if we’re willing, we get to interrogate our very sense of self.

Keep Reading

We Don’t Want What ‘The Music Man’ is Selling

If there’s one thing this revival of The Music Man has it’s fanfare. Both literal (a marching band played outside the theater on opening night) and figurative: since this production was announced it has been loudly heralded as a major moment for Broadway, best signaled by the comically large marquee that adorns the roof of […]

Read More

‘Prayer for the French Republic’ is a Sweeping Family Drama

A multi-generation Jewish family dealing with the legacy of their business told over three hours and three acts on a turn-table set. It’s not The Lehman Trilogy (though the summary also fits), but Joshua Harmon’s latest play, Prayer for the French Republic. Harmon, known for Bad Jews, Significant Other, Admissions, and Skintight, here has hit […]

Read More