‘Prayer for the French Republic’ is a Sweeping Family Drama

A multi-generation Jewish family dealing with the legacy of their business told over three hours and three acts on a turn-table set. It’s not The Lehman Trilogy (though the summary also fits), but Joshua Harmon’s latest play, Prayer for the French Republic. Harmon, known for Bad Jews, Significant Other, Admissions, and Skintight, here has hit his stride, expanding his scope and penning his most successful play to date.

Prayer for the French Republic joins the likes of epic family dramas like Time and the Conways, Arcadia, Clybourne Park, and most recently, of course, The Lehman Trilogy. More than a mere addition to this canon, Prayer for the French Republic makes a case for being the best of the genre, a faultless example of what this type of play can achieve.

The majority of the play concerns the Benhamaous, a French Jewish family living in Paris in 2016 who host their distant American cousin Molly; together they deal with rising anti-Semitism, argue about their Jewish (and French) identity, and question how safe they are in Paris. This evocatively, but subtly, harkens to the older plot of their great-great-grandparents who somehow manage to safely stay in Paris during World War II, while many of their children and loved ones fled or were sent to concentration camps. Multiple generations questioning: when is it time to leave, how long before it’s too late, what the cost of staying could be, and what the pain of migrating might entail.

Harmon masterfully weaves the various generations together to create a compelling drama that feels like a tightly-constructed poem. The playwright does not give everyone equal weight or time on stage: we see much more of the modern-day Behamahous than we do the World War II Salomons, but this is part of the play’s strength, we receive exactly enough of each without overindulging, striking the perfect amount of (im)balance between the thread lines.

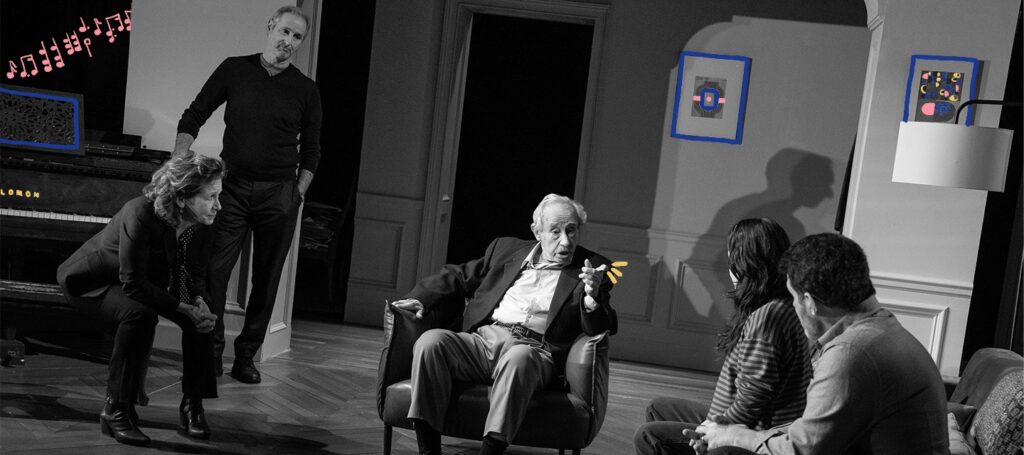

Witnessing the action from center stage is a beautiful piano, an important and unmoving symbol in the play. The Saloman family have sold pianos in Paris for five generations; they have a legacy, a history, and most hauntingly, a reason to stay, even when things are becoming dangerous for Jewish people in Paris.

Set designer Takeshi Kata expertly makes use of a turntable (with the piano as its central axis) and keeps the space spinning, swirling doorframes, walls, bookshelves, and tables, creating various spaces in the past and the present. The puzzle box set has a choreography to it, gracefully pirouetting into unexpected permutations, revealing previously unseen elements and sides of walls that completely change the space.

Aiding Kata’s brilliant use of space is Amith Chandrashaker’s lighting, which manages to keep things in the dark and surprise the audience—never to build tension or mystery, but more to delight and create quiet moments of magic.

These aesthetics fit squarely within director David Cromer’s (The Band’s Visit, The Sound Inside) signature style. Cromer is a master of the minutiae, he revels in small moments in the dark, characters reaching and yearning, leaving things partially unsaid. Harmon’s play provides Cromer a perfect canvas full of narrative gaps, conversational ellipses, stirring debates, emotional parallels, and some unexpected moves—and the director certainly makes the most of it.

Navigating this complex terrain particularly well are the female members of the cast, especially Betsy Aidem (who plays Marcelle, the mother in the modern-day plot), Francis Benhamou (who plays Elodie, her daughter), Molly Ranson (who plays the American cousin), and Nancy Robinette (who plays Irma, the great-great-grandmother in 1944). The four actresses carry the play, keeping things emotionally intense and grounded in very real fears.

Each embodies a type of ferocity and intensity that feels generational: Irma devotedly cares for her son and grandson when they return from a concentration camp, Marcelle obsesses over cleanliness, respectability, and heritage, and Elodie and Molly fight about the history of anti-Semitism and the ethics of the state of Israel.

The play is narrated by Richard Topol (who plays Patrick, Marcelle’s brother) whose storytelling is often necessary to help the audience from losing its way, sadly, Topol is not as strong as his costars. I wondered how different the play might feel narrated by someone else.

In Prayer, Harmon blends themes that rotate around each other, interlocking and entwining in ways that force us to question what we believe in and what we stand for. The sweeping work presents several paradoxical pairings—a strong sense of local culture and a feeling of being an outsider, nationalism and nationlessness, religious pride and a desire to hide it in public, assimilation and separatism, a love for family legacy and a desire to move on—proving that the questions asked by multiple generations of French Jews, “why do they hate us?” and “why should we stay here?” remain painfully relevant.

Keep Reading

‘MJ’ Trips Into the Bio-Musical Morass

MJ, the new Broadway musical about Michael Jackson’s life, is currently thrilling audiences at the Neil Simon Theatre for all the wrong reasons. The show follows MJ―who functions as our narrator―as he balances getting his Dangerous world tour off the ground with interruptions from a documentary filmmaker for MTV who wants an exciting scoop, and […]

Read More

Dominique Morriseau Excavates the Glory of Blackness in ‘Skeleton Crew’

As Black folks like to say, when Dominique Morisseau wrote Skeleton Crew, she put her whole foot in it. For those who aren’t in the know, that means the play is a spectacular blend of lyrical language, political analysis, and delightful humor that prioritizes Black lives and sensibilities over respectability politics. The play follows three […]

Read More