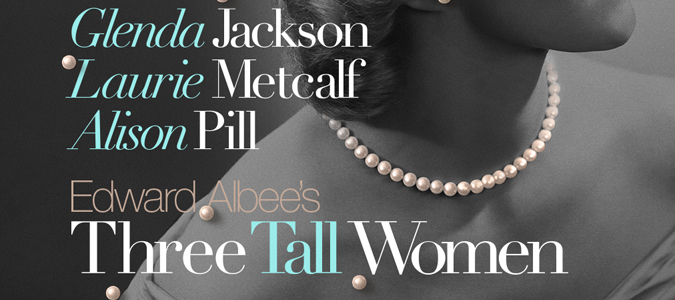

Three Tall Women

Opening Night: March 29, 2018

Closing: June 24, 2018

Theater: John Golden Theatre

Two-time Academy Award® winner Glenda Jackson makes her long-awaited return to Broadway, on the heels of her triumphant reappearance last season on London’s West End after a 25-year absence, alongside three-time Emmy® and Tony Award winner Laurie Metcalf and Tony nominee Alison Pill in the Broadway premiere of Edward Albee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece, Three Tall Women. Hailed as “essential viewing” by Ben Brantley of The New York Times, Three Tall Women has been lauded as a “spellbinding masterpiece” (Time Magazine). In addition to the Pulitzer, the play also won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best Play, and the Outer Critics Circle Award for Best Play. Two-time Tony winner Joe Mantello directs.

BUY TICKETSREAD THE REVIEWS:

March 29, 2018

Her jaw thrust forward like a prow, her elfin eyes belying her regal bearing, her wide-screen mouth wrapping itself around those slashing, implacable consonants — they’re all exactly as you remember them and want them to be. Or if you’ve never experienced them, welcome to the pleasure. Either way, Glenda Jackson is back; even better, she’s back in a role that’s big enough to need her.

Aptly, the name of the role is A.

A is the oldest of Edward Albee’s “Three Tall Women,” which opened on Thursday night in a torrentially exciting production that also stars Laurie Metcalf and Alison Pill. It not only puts an exclamation point on Ms. Jackson’s long-shelved acting career but also serves as a fitting memorial, which is to say a hilarious and horrifying one, to Albee, who died in 2016.

Though “Three Tall Women” won him his third Pulitzer Prize, in 1994, and marked his return from the critical wilderness after two decades of disrepute, this is the play’s Broadway premiere. Joe Mantello’s chic, devastating staging at the Golden Theater was worth the wait.

READ THE REVIEWMarch 29, 2018

March 29, 2018

Watching Glenda Jackson in theatrical flight is like looking straight into the sun. Her expressive face registers her thoughts while guarding her feelings. But it’s the voice that really thrills. Deeply pitched and clarion clear, it’s the commanding voice of stern authority. Don’t mess with this household god or she’ll turn you to stone. Her character, designated “A,” in Edward Albee’s surreal manner, is the dominant figure in the maternal triad that the scribe drew to represent three stages in the life of his own adoptive mother, with whom he had a complicated, not to say rocky relationship. “B” (Laurie Metcalf, a great actress oddly miscast) characterizes the same woman in middle age, conscious of her mental and physical strength, but uncertain of her actual power. “C” (Alison Pill, looking panicked) represents the same mother figure, but in her youth, observing her older selves in horror. From time to time, more realistic roles are suggested for these emblematic figures. “A” is a narcissistic old woman on her deathbed. “B” is her caretaker and “C” does her errands. But reality doesn’t really become them. And aside from the obvious fact that every breath they draw is taking them closer to death, nothing dramatic actually happens on stage.

READ THE REVIEWMarch 29, 2018

Stage acting doesn’t get any better than Glenda Jackson’s performance as the autocratic nonagenarian in Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women, modeled on the adoptive mother with whom the playwright had a famously thorny relationship. On Broadway for the first time in 30 years (23 of which she spent as a member of British Parliament), the two-time Oscar winner shows no trace of rustiness in a characterization of such diamond-hard ferocity you dare not take your eyes off her. It’s an almost ridiculous luxury that in Joe Mantello’s crystalline production of this brittle but moving play about death and self-knowledge, two such accomplished actors as Laurie Metcalf and Alison Pill become supplementary dividends. With its taut structure, psychological acuity, acid-dipped humor and fragmented approach toward anatomizing a single life, not to mention its transparency as a work of an intensely personal nature, Three Tall Women did much to restore Albee’s reputation. After the early plays that had established him as a bracingly original voice in American drama — among them The Zoo Story, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? and A Delicate Balance — the playwright had fallen out of favor through the 1980s, producing work that remained frustratingly cryptic, arid and distancing. Sorting through unresolved feelings toward his adoptive mother in a play he once described as “a kind of exorcism,” Albee’s writing here feels revitalized, which makes this 1994 Pulitzer-winning drama a fine choice for the first Broadway production of his work since his death in 2016.

READ THE REVIEWMarch 29, 2018

Nearly 30 years ago, when Edward Albee was explaining why he’d develop his new play Three Tall Women in Vienna, the great playwright excoriated New York’s commercial stage. Broadway, he said, was not our national theater, it was our national disgrace. Harsh in ’91, absurd beyond measure tonight with the premiere of Joe Mantello’s superb staging of the play’s long-in-coming Broadway premiere. Starring the redoubtable Glenda Jackson, Laurie Metcalf and Alison Pill, Albee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning late-career masterpiece has been given the loving, impeccable production that Albee apparently thought was beyond Broadway’s reach (Scott Rudin leads a team of producers that includes Barry Diller, Eli Bush and James L. Nederlander, among others). When it debuted Off Broadway in ’94, Three Tall Women did seem to make some sort of case for Broadway’s inhospitality to serious drama (intelligent serious, not no laughs serious). Anyone who saw it could only wonder at how such a gorgeous work couldn’t thrive in any home of its choosing.

READ THE REVIEW