The Father

Opening Night: April 14, 2016

Closing: June 12, 2016

Theater: Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

“The Father” offers a fascinating look inside the mind of Andre (Frank Langella), a retired dancer living with his adult daughter Anne and her husband. Or is he a retired engineer receiving a visit from Anne who has moved away with her boyfriend? Why do strangers keep turning up in his room? And where has he left his watch?

BUY TICKETSREAD THE REVIEWS:

April 14, 2016

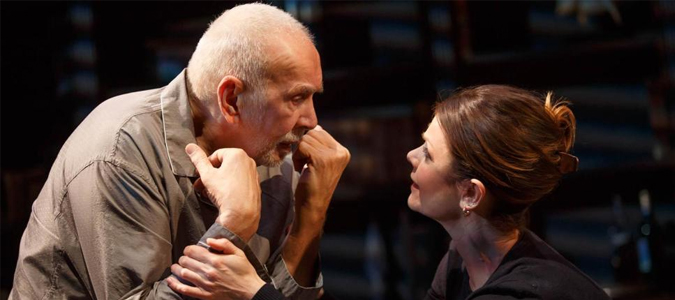

He is a fortress unto himself, but a fortress under siege. The title character in Florian Zeller’s cold-eyed, harrowing “The Father,” which opened on Thursday night at the Samuel J. Friedman Theater, is often found in barricade position. He is an elegant old man, first seen dressed in stony shades of gray, seated obdurately in a gray chair, arms folded defensively. He is holding down the fort of his identity. Everything about his posture says, “Trespass at your own risk.” But because this man — his name is André — is played by Frank Langella, one of the most magnetic theater actors of his generation, there’s no way you’re going to honor his wish for privacy. Before you know it, you’ve walked straight into his head, and what a lonely, frightening, embattled place it is. “The Father,” which has already picked up a war chest of trophies for its French author and its leading men in productions in Paris and London, operates from an exceedingly ingenious premise. It’s one that seems so obvious, when you think about it, that you’re surprised that it hasn’t been done regularly onstage. That’s presenting the world through the perspective of a mind in an advancing state of dementia, making reality as relative and unfixed as it might be in a vintage Theater of the Absurd production. So, as in a play by Eugene Ionesco or the young Edward Albee or Harold Pinter, our hero finds himself in the company of people he is told he knows intimately, but whom he does not recognize. The same is true of the locations he inhabits, which are rarely what he assumes they are. (Or aren’t they?)

READ THE REVIEWApril 14, 2016

With three Tonys on his shelf, Frank Langella knows his way around a Broadway stage. That includes when he’s playing someone lost in the dark clouds of dementia. Meet Andre, the Alzheimer’s-addled title character of “The Father,” a slick but superficial new play. Written by rising-star French author Florian Zeller and translated by Christopher Hampton (“Les Liaisons Dangereuses”), this 90-minute play comes with 15 scenes and a compelling conceit. You must walk a mile in Andre’s slippers to experience what it’s like to lose your marbles. And you will. In Paris, Andre talks to his daughter Anne (Kathryn Erbe, excellent) in a well-appointed flat. His caretaker has quit. Did she walk because he hit her? Or is he the one being abused? Andre, a retired engineer, or so Anne says, acts as if people around him are nuts. So far, so good. But confusion soon sets in as reversals, contradictions and inconsistencies pop up in the script. Factor in vanishing set pieces and characters played by more than one actor, and you relate to Andre. If not Ingrid Bergman in “Gaslight.” It’s a meaty dramatic gambit, though not ground-breaking. “The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time” does something similar with an autistic teenager.

READ THE REVIEWApril 14, 2016

Just last week, Frank Langella was gasping for breath in his role as a Russian spy handler exposed to a deadly virus on FX’s “The Americans.” Here he is tonight on stage at the Manhattan Theatre Club’s Broadway venue, the Friedman Theatre, suffering an equally distraught kind of ravagement in the title role of Florian Zeller’s “The Father” (not to be confused with August Strindberg’s play of the same name). André is his name, and he pads about a spacious apartment in his pajamas. We’re not certain where this apartment is, and neither is poor André, who shows increasing evidence of Alzheimer’s disease. André appears to be in the care of his growingly exasperated daughter Anne (Kathryn Erbe, elegant even in frustration), whose apartment this may actually be. Anne insists her father needs an attendant; André resists even as his memory dims and his actions grow increasingly dangerous. Also as furniture disappears, reappears and shifts around Scott Pask’s warm set, gloomily lit by Donald Holder, and time is an oil slick that may send you careering forward or back without warning.

READ THE REVIEWApril 14, 2016

When Frank Langella first appears as Andre, the elderly Parisian in bristling denial of his failing cognitive faculties in “The Father,” he’s ensconced in his elegant apartment, designed in immaculate detail by Scott Pask with a stylish mix of antique and modern. Or is it the home of Andre’s daughter, Anne? Over the 90-minute course of this slippery one-act, the furnishings vanish or are rearranged piece by piece with impressive theatrical sleight of hand. The teal walls are bare by the end, with just a hospital bed center stage in an unfamiliar room that has become a cell. Andre is left alone there in a state of terrified disorientation, with only a stranger to provide coolly professional comfort. As a visual metaphor for the advancing isolation of an unraveling mind surrendering to dementia, the staging is certainly eloquent. It’s matched by the powerful work of Langella, conveying the painful freefall from eroding dignity into infantilized helplessness. Kathryn Erbe is equally persuasive as Anne, the daughter who is either skipping off to London to pursue her own happiness or selflessly straining her marriage to care for her ailing parent, depending on which version of Andre’s muddled reality you accept. But French playwright Florian Zeller’s drama — adapted in English by Christopher Hampton and premiered to considerable acclaim in London — is a stubbornly unemotional experience, its approach too cerebral and distancing to achieve the shattering impact that the performances demand.

READ THE REVIEWApril 14, 2016

The script for “The Father” gives it an evocative subtitle: “A Tragic Farce.” There are no slamming doors in Florian Zeller’s 2012 French drama, but there is plenty of mistaken identity. André (Frank Langella), an elderly former engineer, is losing his mind to dementia, which puts an increasing burden on his patient daughter Anne (Kathryn Erbe, underplaying well) and her partner, Pierre (Brian Avers). As often as not, he doesn’t recognize them, and his confusion is literalized on stage: Anne, Pierre and caretaker Laura (the gifted Hannah Cabell) sometimes appear in the form of different actors, identified only as Woman (Kathleen McNenny) and Man (Charles Borland). The play keeps its audience in a continuous state of disorientation, possibly moving around in time, smudging the lines between reality and misperception. Not even Scott Pask’s tastefully appointed set remains stable. Between scenes, the stage goes dark and lights flash around the proscenium like synapses. And when a new scene begins, something is missing: small things at first, like books and artwork, but eventually major items of furniture. (Jim Steinmeyer is credited as Illusion Consultant.) André’s life is disappearing before our eyes.

READ THE REVIEW