Pope/Bettany Elevate ‘The Collaboration’ Into Art Worth Contemplating

One of them paved a path of his own ascending to artistic godhood by glorifying the mundane; the other painted SAMO (meaning the Same Old Sh*t) criticizing the very idea of repetition. One of them broke down the wall between art and business; for the other, walls didn’t mean a thing. One saw beauty, immortality, and the American Dream in Campbell soup cans and bananas, yet found his own ugliness unbearable; the other would rather art be grotesque, angry, and violent, but maintained that there’s mystifying power between the raw edges of crude brushstrokes, and with the right symbols and colors, art could save lives.

And, once upon a time – the ‘80s to be exact, theirs was a friendship that raised not only eyebrows and auction prices, but also intrigue: Jean-Michel Basquiat (Jeremy Pope) and Andy Warhol (Paul Bettany) were an unlikely pair, and yet, taking a deeper look into their individual pasts, and clearing away the glamour that shrouds them, there lies an inevitable connection. That famous collaboration is at the center of Anthony McCarten’s new play which remains surfacely cerebral rather than thought-provoking.

The well-honed production (directed by Kwame Kwei-Armah) brings the hottest downtown gallery opening to the stage of the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, complete with a DJ (the Brooklyn-based, genderqueer artist who goes by the stage name theoretic) who creates an atmospheric preshow that drops the audience right into it. The discs turn as time spins back and we all get to, briefly, be in the room where it happened: the famous clash of artistic titans, between the king of pop art and the king who created his own crown.

The Collaboration serves audience members a fictitious account of Basquiat and Warhol’s time together around their shared canvases between 1983 and 1985. It was a working relationship that they were, based on the play, ostensibly forced into by Bruno Bischofberger (Erik Jensen), the Swiss art dealer who represented them both. The hope, from the practical Bischofberger, is that perhaps Basquiat, the rising star, would bring Warhol back to relevancy, and that Basquiat, similarly, could get even further ahead riding Warhol’s fame.

Though it sets up a dramatic tension for the collaborators to be somewhat antagonistic, providing ample opportunities for the two performers to do verbal jousting, and wax poetic about their respective art philosophies, which is indeed the meat of the play, it also forced me into a place of cognitive dissonance. Art historians in the audience most likely would know that in reality, a young Basquiat had sought out Warhol as a street artist and sold the latter a few postcards, after which they had formed a friendship, prior to co-oping a studio (their duet was previously a trio along with Francesco Clemente). And for the audience members who are encountering the two for the first time, I wonder if it’s a responsible choice to alter actual historical events.

Or rather, was it even worth it? Especially since the play doesn’t offer a new point of view, or illuminate further on the phenomena that were Basquiat and Warhol. Instead, fragments of interviews, like questions originally asked by Rene Ricard (but in this production coming from Warhol’s mouth), were forced into dialogue. The play, therefore, fails to give a truthful representation of how the collaboration started and doesn’t show you what the collaboration led to in a meaningful way.

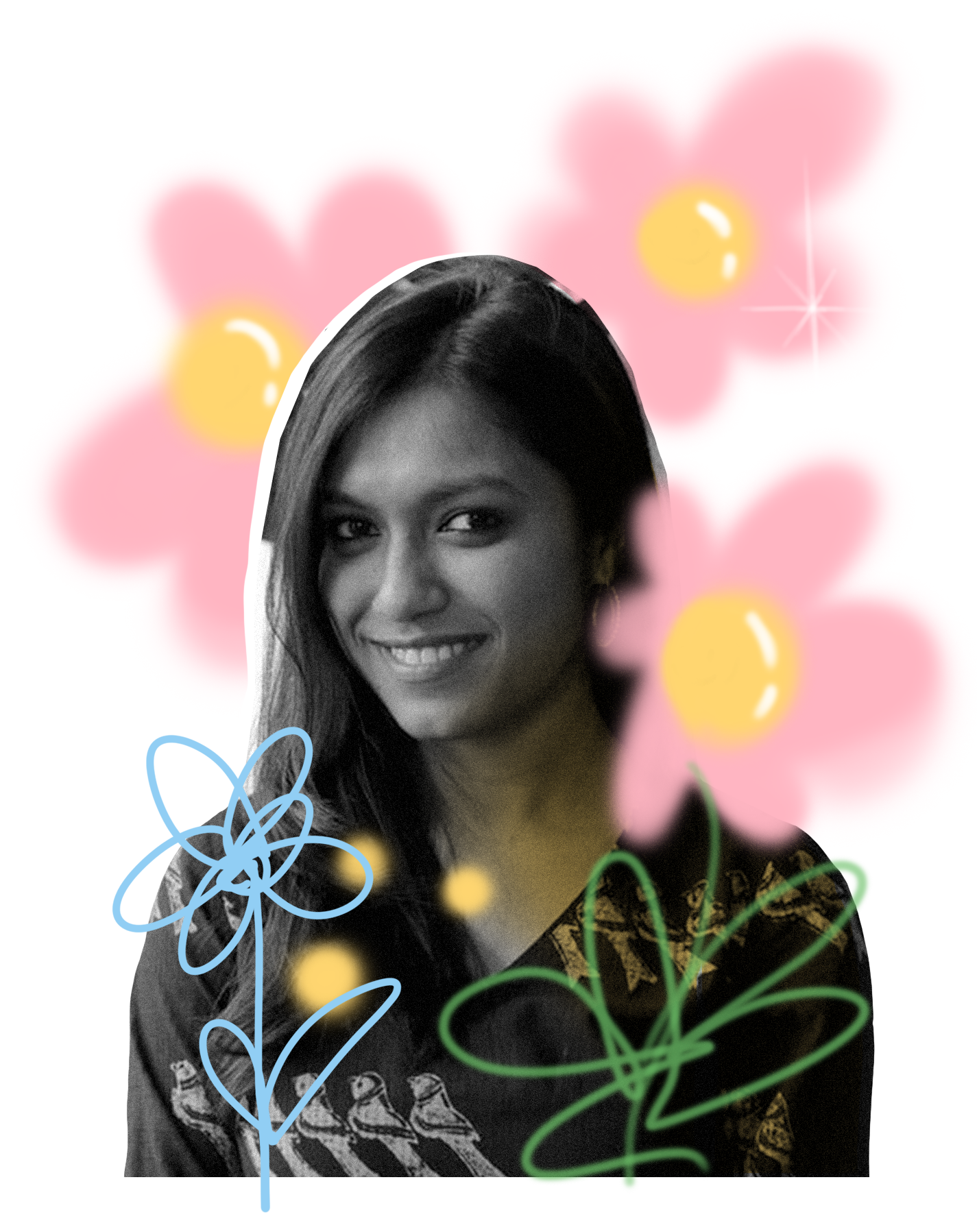

Still, the play, through its lead performers, successfully captures the complexity of two characters that often take on too much of a mystifying aura in artistic representations. The scenes between the two are marvels to behold: Pope’s Basquiat has a childlike wonder, and an electrifying presence, as the eccentric, somewhat boastful (with the right to be) wavemaker – he’s also chaos personified in contrast to Warhol, whom Bettany portrays with meticulousness and grace, as a legend who also seems to be afraid of his own shadow.

It’s almost impossible not to think of John Logan’s Red, which also focused on the role art plays in society through the eyes of Mark Rothko. As a two-hander, the more stylized dynamics were sustained in a more succinct way between Rothko and his bright-eyed young apprentice in Logan’s play. In The Collaboration, however, realism almost got in the way, as Bruno and Maya (a composite character representing Basquiat’s romantic partners portrayed by Krysta Rodriguez) become plot devices rather than add deeper layers to the story.

Between the captivating performances of Pope and Bettany, and the thoroughly impressive production design (mostly notably Duncan McLean, who is single-handedly converting me into a believer in the efficacy of projection design with his use of every surface as means of additional storytelling), I believe The Collaboration is a production worth to be reckoned with. It’s a shame, however, that I couldn’t find a clear point of view from the play itself, even though both artists provided plenty.

Keep Reading

Complex Men and Caricatures of Women Are Caught ‘Between Riverside and Crazy’

Walter “Pops” Washington, as he self-describes in Stephen Adly Guirgis’ Pulitzer-winning play Between Riverside and Crazy, is “a flesh and blood, pee standing up, registered Republican.” He is also a litigious former cop caught within the crossroads of bureaucracy, racism, life as a widower, and a fast-gentrifying Riverside Drive. He also happens to be Black. […]

Read More

Slickly, Albeit Slowly, ‘Some Like It Hot’, Dances Towards Thoughtful Representation Onstage

If there was an altar to American desirability and mystique, very few people would hold as much space in it as Marilyn Monroe. We feel possessive about her legacy, in a way that drives us to collectively defend her when a TV show fetishizes her life’s traumas. Monroe, in many different ways, signifies America and […]

Read More