Privacy

Opening Night: July 18, 2016

Closing: August 7, 2016

Theater: Joseph Papp Public Theater

Inspired by the revelations of Edward Snowden, Privacy explores our complicated relationship with technology and data through the funny and heart-breaking travails of a lonely guy, who arrives in the city to figure out how to like, tag, and share his life without giving it all away. The play uncovers what our technological choices reveal about who we are, what we want and who’s keeping track of it all. This provocative theatrical event will ask audiences to charge their phones, leave them ON during the performance and to embark on a fascinating dive online and into a new reality where we’re all connected…for better or worse.

BUY TICKETSREAD THE REVIEWS:

July 18, 2016

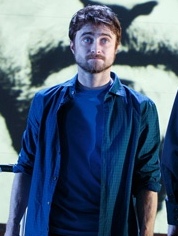

Grim tidings are spread with great cheer in “Privacy,” James Graham and Josie Rourke’s perky investigation into the consequences of living your life online. This London-born production from 2014 — which opened in an updated, Americanized version (“Brexit” jokes!) at the Public Theater on Monday night — stars a charmingly woebegone Daniel Radcliffe as a writer who has conflicted feelings about all his relationships, but especially the one with the internet. The presence of the man who played Harry Potter isn’t the only reason “Privacy” has become one of New York’s hottest tickets. Viewed as a play, it is neither as profound as it aspires to be nor even entirely cohesive. But it ingeniously recreates that most venerable of entertainments, the magic show, in a form ideally suited to the second decade of the 21st century. Like the work of celebrated prestidigitators (like David Copperfield, Penn & Teller) and mentalists (Derren Brown, the Amazing Kreskin), “Privacy” dazzles and baffles by seeming to know exactly what selected audience members are thinking — and who they are, what they’ve done and where they’ve been. And like such traditional fare, this show fully intends to make you say “wow!” again and again. But “Privacy” goes one painful, enlightening step further by always putting the “ow!” in “wow!” That’s because the secret-wranglers onstage — embodied by a vivacious supporting cast — are not relying principally on human intuition or hidden accomplices or bait-and-switch techniques. No, they can look deep into what passes for your soul these days because they have access to your smartphones. [ “Privacy” is part comedy, part documentary, part lecture-demonstration and part fourth-wall smasher ] In other words, Big Brother and company have replaced the dashing figures who pull rabbits out of hats. Though the play quotes the phrase “be not afeard” from Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” the purpose of “Privacy” is to scare you silly, through only seemingly silly means. By the way, one of the folks who recites those words happens to be Edward J. Snowden — the exiled, whistle-blowing computer whiz and former National Security Agency contractor — whose appearance here is made possible by the double-edged technology that gives “Privacy” its style and substance. I think it’s O.K. to mention Mr. Snowden. (His videotaped appearance in “Privacy” has already been reported.) Like most magic shows, this one ends with a statement from its star (Mr. Radcliffe), asking that we not give away its manifold surprises for future audiences. Since one of the main points of the evening is that no secret is keepable anymore, this feels like a sadly quixotic request, a paradox that Mr. Graham’s script doesn’t exploit as dizzyingly as it might. But to avoid being stigmatized as a spoiler, I will honor Mr. Radcliffe’s plea. Which doesn’t leave me with a whole lot to talk about, except in abstract terms, and the coolest tricks in “Privacy” involve very detailed specifics. Like personal specifics. Like your personal specifics. There is a reason that, for once in a New York theater, you are encouraged to leave your smartphones on throughout the show. Heck, this production even provides free Wi-Fi for you. All the better to see you with, my dears. I’m making “Privacy” sound creepier and more compelling than it ultimately is. As written by Mr. Graham (the author of the terrific British Parliament docudrama “This House”) and Ms. Rourke (the artistic director of Donmar Warehouse in London, where “Privacy” originated), this production is respectful about never crossing certain lines with those watching it, though it promises that it could if it wanted to. The lost soul portrayed by Mr. Radcliffe, known simply as the Writer, is treated less gently. When the play begins, he has just ended a relationship with someone to whom he refers with the gender-neutral pronoun of “they.” Even speaking to his new psychiatrist, Josh Cohen (Reg Rogers), the Writer is coy about “they” — who appears to have walked out precisely because the Writer is so withholding of his innermost self. Being English, he says, he is an instinctively private person, with “a phobia of being known.” In an effort to break down those self-isolating walls, he crosses the Atlantic to New York City, where his ex now resides. (It turns out to be a he, for the record.) Little does the Writer know, at this point, how completely known he is already, simply because he uses his smartphone and laptop. On hand to edify him are a host of fantasy versions of real people who embody different sides of the argument on public versus private selves. Such academic cultural commentators as Sherry Turkle, Jill Lepore and Daniel Solove are introduced to debate the pros and cons of virtual communality. (The real Ms. Turkle, drolly played here by Rachel Dratch, will be participating in a “Privacy” forum at the Public on Aug. 1.) Retailing entrepreneurs and Silicon Valley executives; representatives of government surveillance agencies; politicians and journalists (among them, Ewen MacAskill, a reporter for the London publication The Guardian who helped break the Snowden story) — they also appear to explain how completely we expose ourselves every time we log on. They are brought to chipper, slightly cartoonish life by a cast appealingly rounded out by De’Adre Aziza, Raffi Barsoumian and Michael Countryman. The technical team — which includes Lucy Osborne (sets), Richard Howell (lighting) and Duncan McLean (projections) — adroitly conjures a world in which what we see on tiny screens seems to grow into three dimensions, even as so-called real life flattens out. The parts of the show I can’t talk about — the many audience participation sequences — are both its giddiest and most sobering. “Privacy” doesn’t provide much material that hasn’t been rehashed many times in newspaper and magazine (and blog and vlog) essays. It can feel rather like one of those middle school instructional films that use a likable animated creature (a talking dinosaur or skeleton, maybe) to keep its distractible young viewers hooked. The scene in which I felt most engaged, confused and affected involves little techno sleight of hand, just a very deft performer (that would be Mr. Radcliffe) treading water in an improvisational sequence. Or was it? I can say no more. But it’s a relief to be able to report that “Privacy” shines brightest when it comes down to a single actor plying centuries-old tricks of his trade.

READ THE REVIEW