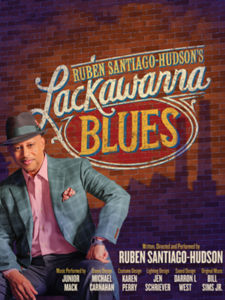

Lackawanna Blues

Opening Night: October 7, 2021

Closing: October 31, 2021

Theater: Samuel J. Friedman Theatre

Tony Award winner Ruben Santiago-Hudson returns to MTC for the Broadway debut of his brilliant solo play celebrating the strong, big-hearted woman who raised him: Miss Rachel. In a 1950s boarding house outside Buffalo, Nanny, as she was affectionately called, opened her doors to anyone and everyone in need of kindness, hope, compassion, and care. Giving a tour-de-force performance accompanied by live music written by acclaimed composer Bill Sims Jr. and performed by Blues Hall of Fame Guitarist Junior Mack, Santiago-Hudson embodies more than 20 vibrant characters, creating a richly textured reminiscence that’s inspiring, uplifting and right at home on Broadway.

BUY TICKETSREAD THE REVIEWS:

October 7, 2021

He grounds us in the details, which brings not just these characters, but also a whole town to life: the way a woman pops her hips, the way a man coughs, even the particular tint of the Lackawanna snow. After all, people may think the blues are about heartbreak, but to get to heartbreak, you first have to pass through love.

READ THE REVIEWOctober 7, 2021

But Lackawanna Blues is, after all, a memory play, and Santiago-Hudson makes no bones about presenting the ghosts (and occasional monster) of his childhood with an enveloping and inviting compassion. He does them proud.

READ THE REVIEWOctober 7, 2021

Santiago-Hudson slides smoothly into dozens of roles in this 90-minute collage of vignettes, including Nanny, and many of the people he plays are wounded: older men with one leg or one arm or no fingers or no marbles and no place else to go. (Even the animals in the play are damaged: a one-eyed cat, a three-legged dog.) They have colorful names like Sweet Tooth Sam, Numb Finger Pete and Ol’ Po’ Carl—a heavy drinker who, in his malaprop-prone wording, suffers from “the roaches of the liver”—and several serious criminal records. True to Miss Rachel’s example, the show mostly approaches them without judgment or condescension.

READ THE REVIEWOctober 7, 2021

All great blues songs have a timeless quality, so it’s entirely fitting that Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s solo show “Lackawanna Blues” still gleams like a newly minted coin some 20 years after it was first produced. In the Broadway production at Manhattan Theater Club’s Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, Santiago-Hudson reprises his vibrantly virtuosic performance, guaranteeing that this memoir of his youth in a boarding house retains all the lively humor and radiant feeling of the original production at the Public Theater.

READ THE REVIEWOctober 7, 2021

Lackawanna Blues convinces me that there is very little that Santiago-Hudson cannot do. What he does most masterfully is exorcising the graceful and benevolent ghost of a woman whose kindness in the face of racism and anger in the face of injustice are nothing short of radical. It is at that moment, that I miss the bodily presence of that woman—the real Ms. Crosby—on stage. The presence of those safe hands that fed, clothed, and housed people (“like the government if it worked”, as they say in the play) in the middle of times where each one of those rights have become contentious.

READ THE REVIEW