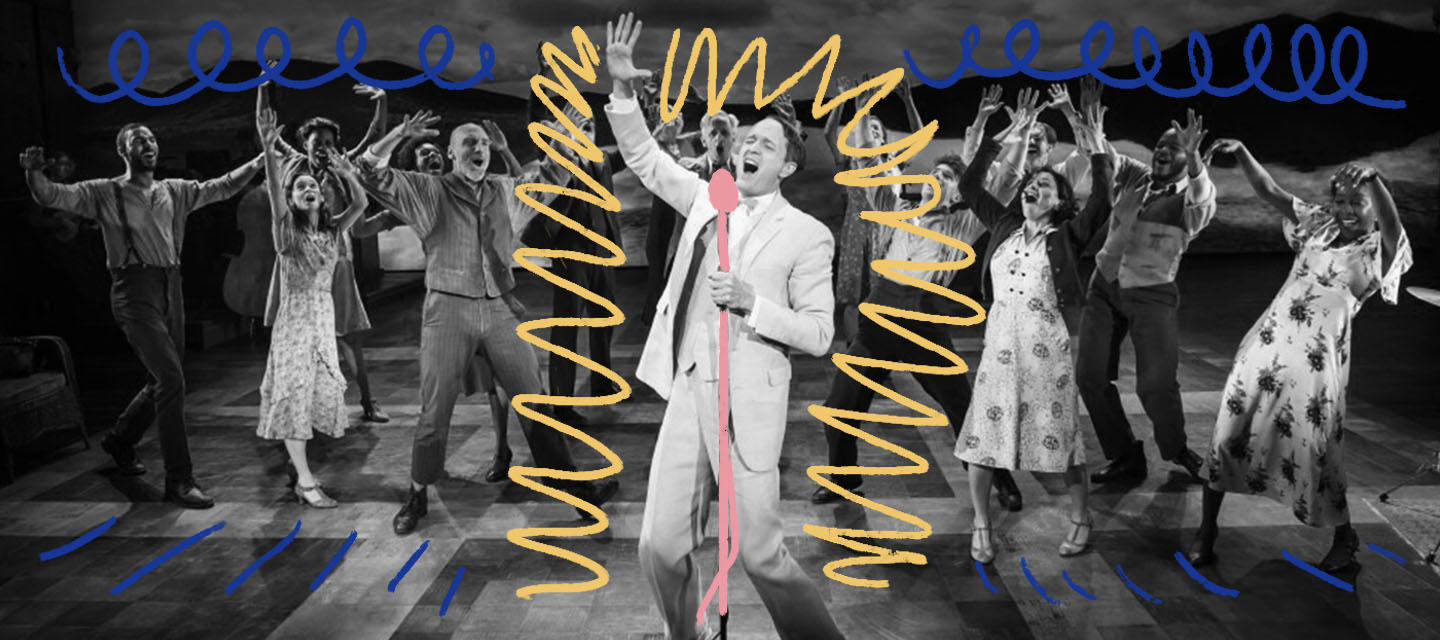

Girl From The North Country

Opening Night: March 5, 2020

Theater: Belasco Theatre

Girl From The North Country is set at a guesthouse where a group of wanderers cross paths. Standing at a turning point in their lives, they realize nothing is what it seems. But as they search for a future, and hide from the past, they find themselves facing unspoken truths about the present.

BUY TICKETSREAD THE REVIEWS:

March 5, 2020

Some people think Bob Dylan’s music is depressing — and in “Girl From the North Country,” Conor McPherson makes the case by setting more than twenty of Dylan’s songs into a surprisingly sturdy narrative about the residents of a seedy boarding house in Duluth, Minnesota, at the height of the Depression in 1934. Although individual tunes like “Slow Train” and “Duquesne Whistle” feel as if they were written in direct response to the Great Depression, other songs don’t always suit the specific dramatic situations in which they’re set. But overall, the morose music captures the bleakness of the period and the down-and-out hopelessness of those Americans who barely lived through it. So does the bare-bones wooden set by Rae Smith, who also designed the studiously appropriate costumes of subdued colors and tiny prints. In particular, Mark Henderson’s melancholy lighting design casts shadows everywhere, including the faces of the actors, who have that wan, hard-times look of people who eat to stay alive, but don’t ever have dessert.

READ THE REVIEWMarch 5, 2020

In case you hadn’t noticed over the last five or six decades, Bob Dylan can’t be contained, not by any particular genre, persona, creed or even voice, and the same can mostly be said for Girl From The North Country, the musical, written and directed by Conor McPherson, that transports the hits and deep-cuts of a peerless songbook to a Depression-era, crossroads-of-humanity boarding house. Opening tonight in a Broadway production that both focuses and somewhat constricts the musical that seemed more physically expansive, more tonally dreamlike, in its 2018 Off Broadway incarnation, Girl From The North Country nonetheless remains a revelation in its uncanny interpretations of even the most familiar Dylan songs.

READ THE REVIEWMarch 5, 2020

A nation is broken. Life savings have vanished overnight. Home as a place you thought you would live forever no longer exists. People don’t so much connect as collide, even members of the same family. And it seems like winter is never going to end. That’s the view from Duluth, Minn., 1934, as conjured in the profoundly beautiful “Girl From the North Country,” a work by the Irish dramatist Conor McPherson built around vintage songs by Bob Dylan. You’re probably thinking that such a harsh vision of an American yesterday looks uncomfortably close to tomorrow. Who would want to stare into such a dark mirror? Yet while this singular production, which opened on Thursday night at the Belasco Theater under McPherson’s luminous direction, evokes the Great Depression with uncompromising bleakness, it is ultimately the opposite of depressing. That’s because McPherson hears America singing in the dark. And those voices light up the night with the radiance of divine grace.

READ THE REVIEWMarch 5, 2020

Far closer to Eugene O’Neill’s “The Iceman Cometh” than “Mamma Mia!,” the beguiling and beautiful new show at the Belasco Theatre is hardly a Bob Dylan jukebox musical. Sure, the score for “Girl From the North Country,” an ensemble piece that showcases Mare Winningham in an extraordinarily intense and musically compelling performance, is comprised of more than 20 of the legendary protest-warbler’s iconic compositions, ranging from “Slow Train” to “Like a Rolling Stone” and “All Along the Watchtower” to “Forever Young.” But instead of the usual trite Broadway biographical trajectory of star gets plucked from nowhere, impresses the suits of the music biz, gets screwed over by those same suits, gets depressed and then has a thrilling comeback, the actual context of the gravely Dylan’s famously reclusive life has little or nothing to do with this show.

READ THE REVIEWMarch 5, 2020

No disrespect to Bob Dylan, one of the greatest songwriters in modern American music, but hearing his tunes sung by the melodious voices in Girl From the North Country is a revelation — the second time even more than the first. Moving to Broadway after a hit 2018 run at the Public Theater, this brilliantly conceived project from Irish writer-director Conor McPherson could be called the anti-jukebox musical. Rather than being forcibly wedged into the narrative, the songs are used with imagination and a sweeping amplitude of feeling to deepen the mood, enrich the characters and liberate their inner voices. The result is a rapturous act of theatrical storytelling.

READ THE REVIEW