“Ain’t No Mo’” is a Ravishing Bouquet of Blackness

The revolutionary power of Black joy takes center stage in the Broadway debut of Jordan E. Cooper’s ravishing play, Ain’t No Mo.’ Much like its 2019 production at the Public Theater, this uproariously gut-punching transfer posits a world wherein every Black person in the United States is offered a one-way ticket to Africa.

Far from flattening out Black identity as a monolith, over the course of six specific vignettes, Cooper thoroughly illustrates the multitudes of Blackness. What unites his sui generis characters is that they lead with undefeated fervor that is wrapped in love and inspired by humor.

In Ain’t No Mo’, that is true whether the characters are cackling profanely from a church pulpit, sassily shepherding passengers to safety, fighting to terminate a life, shucking and recognizing their complicity on reality television, burying themselves in the sunken place, or coming to terms with the possibilities of freedom.

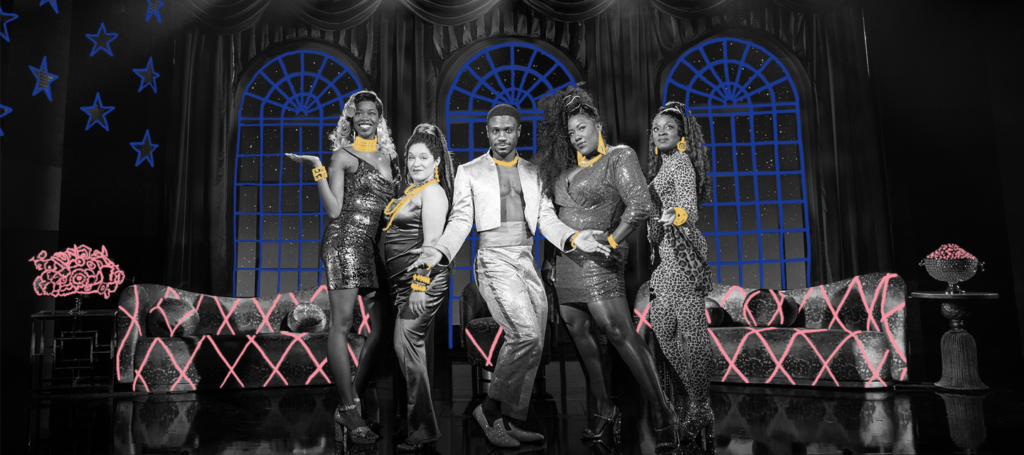

Cooper is featured between scenes as Ain’t No Mo’s focal point, during which he plays Peaches―a statuesque drag queen who ribs passengers about Black stereotypes, such as the proclivity for lateness and stubbornness. In these moments, Peaches addresses the audience directly as if they were attendants of a drag brunch performance, minus the bottomless mimosas.

Under Stevie Walker-Webb’s generous direction, it becomes clear that Peaches is a response to the white slavers who began kidnapping Africans over 500 years ago. Rather than whip us into submission, she flirts with and teases us until we are eager to board the transcontinental ride to supposed freedom. That seduction game reveals a major tenet of this production―dealing with the consequences of one’s actions and acknowledging that moving in one direction means leaving something behind.

That is most clear during a visit with a bourgeois family who discover that their father buried his and their Blackness in their cellar, in order to attain wealth. When that Black spirit (played by Crystal Lucas-Perry with an all-the-awards-winning energy) appears, rather than risk being discovered or embracing who they could be, they repeatedly murder her. Interestingly, though their actions felt horrible to me, it was clear that Cooper wrote the scene without derision for wealthy Black people. Rather the scene functions as a bicameral Rorschach test, wherein people who agree with doing whatever it takes to succeed in white society will feel absolved, if not understood.

That’s what makes Ain’t No Mo’ so compelling. Cooper and Walker-Webb consider all sides of an argument in each scenario so that one isn’t entirely sure whether their neighbors are in agreement regarding what is right or bad.

Though many critics have described the play as a farce or camp, as a Black man, I consider it a realistic documentary of being Black in this American life, through a comic lens. Much like Jordan Peele’s film documentary of being Black in New England, Get Out.

Cooper returns to the theme of selling out with an evisceration of the Real Housewives franchise, during which wealthy Black performers realize that their cooning for the coin has empowered “transracial” imitators―such as Rachel Dolezal or the many white academic “experts” of Black scholarship―to prostitute warped versions of the culture. In this instance, Rachonda (Shannon Matesky in a show-stopping coup of brilliant buffoonery) reveals to her complicit fictional castmates that commodifying your culture means inviting the world to devour you.

But the most meaningful scene comments on the carceral system. In another stand-out performance, Lucas-Perry plays a stoic and withdrawn prisoner who is on the brink of being released so that she can participate in the exodus. But when it is time to collect her belongings, she demands that the time she was lost, that she can never reclaim, be returned to her. It’s a quiet performance that suddenly blazes forward only to vanish into a sinkhole as the prisoner finally lets go and decides to take a chance on possibly being disappointed again.

Lucas-Perry has already impressed audiences with her leading performance in the revival of 1776―which she departed early in order to participate in Ain’t No Mo.’ Though all of her castmates are stellar, in these moments she reveals herself to be an entire constellation of luminosity.

Cooper takes us home with a devastating final performance as Peaches who learns that even though she has gotten everyone to safety, no one bothered to make sure that she made it. While attempting to collect a beautifully designed bag that is filled with Black glory, a series of spectacular effects―that must be seen to be believed―erupt across the stage.

This sequence has numerous interpretations but ends with the sacrifice of a Black queer person. Cooper leaves us with a salient critique of anyone who calls for Black unity but fails to make space for the multiple possibilities that exist within Blackness.

Keep Reading

‘A Beautiful Noise’ Serves Cheap Thrills but No Drama

Using therapy as the framing for a musical play is a theatrical cheat. In such instances, rather than develop nuanced motivations or put effort into finessing a resolution, playwrights telegraph that their characters are working through trauma and are to be forgiven for anything they do or say―no matter how boring or formulaic. And so […]

Read More

If the Refreshing ‘KPOP’ is the Future of Broadway, Consider Me a Stan

Against all expectations for a behind-the-scenes musical drama, KPOP’s storytelling is as sophisticated as its high-octane performances. Though the newly-opened Broadway musical at Circle in the Square Theater was a hit during its pre-pandemic run at Ars Nova, I was prepared to hate-watch it. Why? Because I wince whenever I hear the cheesy bops of […]

Read More