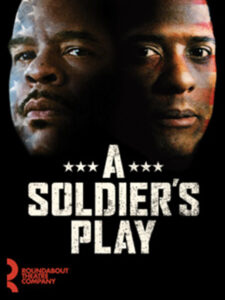

A Soldier’s Play

Opening Night: January 21, 2020

Closing: March 15, 2020

Theater: American Airlines

1944. A Louisiana Army base. A sergeant is murdered—and the crime, with its masterfully unfolded investigation, triggers a gripping barrage of questions about sacrifice, service, and identity in America. A hair-raising drama that reverberates with the “authentic and exciting pulse” (Ben Brantley, The New York Times) of mystery, Charles Fuller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece rockets onto Broadway for the first time, starring three-time Tony nominee David Alan Grier and two-time Golden Globe nominee Blair Underwood and directed by Tony Award winner Kenny Leon (A Raisin in the Sun).

READ THE REVIEWS:

January 22, 2020

Now, that’s what I call a play! Charles Fuller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning drama “A Soldier’s Play,” now being revived on Broadway by Roundabout Theatre Company, packs plenty of dramatic tension into smoldering issues of racial justice and injustice, military honor and dishonor, and the solemn struggle to balance their harrowing demands on characters who are only human. A superb all-male ensemble, under the powerhouse direction of Kenny Leon, attacks this knock-your-socks-off drama with intense emotional passion and intellectual courage. Breathe slowly and keep your heartbeat steady if you hope to make it through this one without breaking up into little pieces.

READ THE REVIEWJanuary 21, 2020

But the themes and the structure can sometimes seem at odds. Not, apparently, as originally produced by the Negro Ensemble Company, when Frank Rich, writing for The New York Times, called it “a mature and accomplished work.” Nor in the excellent 1984 movie, retitled “A Soldier’s Story,” which uses plenty of close-ups to keep the focus on the characters instead of the plot machinery. Onstage, though, the loud ticktock of the investigation too often drowns out the emotion — an effect perhaps enhanced by the flattening of the genre brought on by endless “Law & Order” spinoffs and reruns. In any case, whether “A Soldier’s Play” is a great stage drama regardless of its flaws is something its bumpy but worthy Broadway debut, directed by Kenny Leon for the Roundabout Theater Company, cannot answer. Despite some powerful acting, it is too distracted to make the case.

READ THE REVIEWJanuary 21, 2020

The last few years have seen an explosion of formally and thematically bold work by African American dramatists addressing race-related issues from stinging contemporary perspectives — playwrights like Dominique Morisseau, Jackie Sibblies Drury, Jeremy O. Harris, Robert O’Hara, Aleshea Harris and Antoinette Nwandu, just for starters. So the belated arrival on Broadway of Charles Fuller’s 1982 Pulitzer Prize winner, A Soldier’s Play, risks looking like a throwback to more old-fashioned, conventional drama. Yet in the hands of director Kenny Leon and a terrific ensemble, this period piece about corrosive self-loathing bred out of institutionalized racism remains powerful theater.

READ THE REVIEWJanuary 21, 2020

Nearly 40 years after its celebrated Off Broadway debut and subsequent hit movie adaptation, Charles Fuller’s Pulitzer Prize-winning A Soldier’s Play, opening tonight on Broadway at the Roundabout’s American Airlines Theatre, has lost little of its power. Even in a Broadway landscape that could give home to the explosive Slave Play, Fuller’s 1981 mystery remains a bracing slap of a drama, a thoughtful examination of American bigotry and the many tolls it exacts. With three-time Tony nominee David Alan Grier and a commanding Blair Underwood leading a first-rate, 12-member cast, this Soldier’s Play (adapted as A Soldier’s Story for the 1984 film) moves with all the precision of a military cadence. The production is not without its missteps – a few self-conscious moments seem like gratuitous elbow jabs to make sure we understand the contemporary relevance – but director Kenny Leon drives the narrative with a solid feel for momentum.

READ THE REVIEWJanuary 21, 2020

As directed by Kenny Leon in its first Broadway production, however, the play is sturdy instead of creaky: Like the bare wood of Derek McLane’s set, it gets the job done, and it provides a platform for powerful moments and performances. The steel-jawed Underwood, sympathetic yet commanding, provides a stoic axis for the production; Davenport, often wearing sunglasses, keeps his cool, even when his rank unsettles his white colleagues and subordinates. (Jerry O’Connell, playing a conflicted white captain, looks like he’s about to burst a blood vessel throughout.) Grier is Underwood’s equal and opposite: He brings rage and pathos to the role of the cruel Waters, “split by the madness of race in America,” who is twisted with contempt for other black men—especially Southern ones—whom he considers an embarrassment to the race. (He dismisses them as “geechies” and worse.) The play is in many ways his tragedy. As Private C.J. Memphis (J. Alphonse Nicholson), a guitar-playing “Mississippi boy” for whom Waters has a special disdain, kindly observes: “Any man ain’t sure where he belongs must be in a whole lotta pain.”

READ THE REVIEW