‘for colored girls’ Is a Timeless Movement in Compassion

After playwright Ntozake Shange’s death in 2018, her sister—the playwright Ifa Bayeza—said, “I don’t think there’s a day on the planet when there’s not a young woman who discovers herself through the words of my sister.” As I watched the revival of Shange’s “choreopoem” for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, Bayeza’s words rang true and loud.

This revival is directed by Camille A. Brown, the first Black woman to choreograph and direct a Broadway production in 65 years. Brown, who hadn’t even been born when the play premiered on Broadway in 1976, connected to Shange’s work to the point she expressed “I’ve been there” to Playbill. For colored girls, as much as it is Shange’s words, is equally Brown’s play.

It is a legacy that’s been handed down, and, irrespective of which part of the beautiful colored spectrum we see ourselves in—it is our play. The generosity with which the play shares its worlds with the women watching it is its greatest strength.

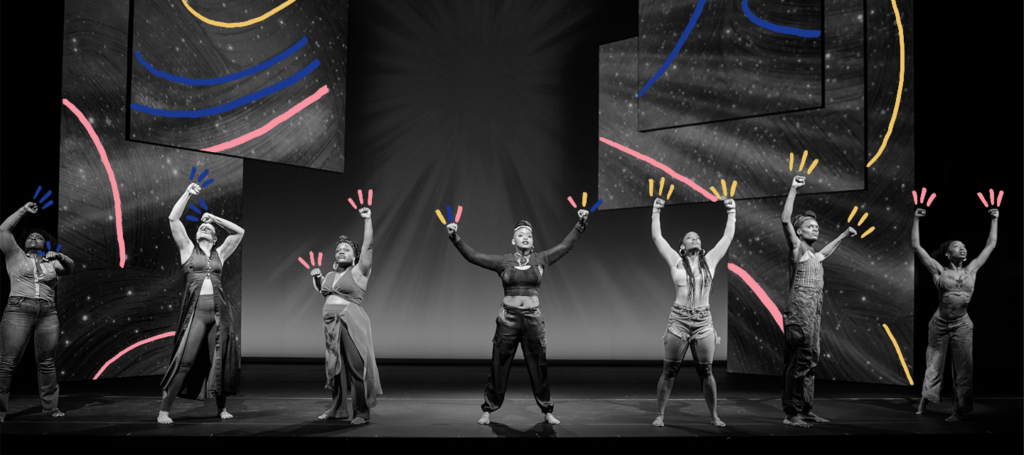

For colored girls which combines poetry, prose, dance, play, and music, is about seven Black women who share space, stories, joys, and sadness through movement—all in a way that immerses the experience in Black joy and resilience. Black women stand to be threatened in the gravest ways as they stand in the intersections of race, class, gender, and sexuality. The experience of living through such lives is so layered and nuanced that it often is impossible to fit them into artworks—least of all a play that runs for 90 minutes.

Both Shange and Brown embody the lives in the play, and they believe in a sense of movement that both surpasses the limits the society puts on the lives of Black women and connects the many selves the women on and off stage inhabit.

It is also a movement in compassion that is ever-forgiving. As bell hooks writes in We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity, “When women get together and talk about men, the news is almost always bad news. If the topic gets specific and the focus is on Black men, the news is even worse.” The women in for colored girls talk about men—Black men—and the news is often bad, but the text of the play never makes that its focus, thereby keeping the “worse” that hooks speaks of, at bay.

The focus remains, steadfastly, on the women. As the women sing and dance, their grief—often a direct fallout of the violence and heartbreak Black men inflict upon them—peeks out, and it quickly turns into a collective rage that is sad and heartbreaking but never threatening. It reminds me of bell hooks again when she asks, “…how do we hold people accountable for wrongdoing and yet at the same time remain in touch with their humanity enough to believe in their capacity to be transformed?”

For colored girls is a play about the nimbleness and agility with which Black women withstand, transform, and survive—and by its staging, it invites the audience to believe in this transformation, and for them to be a part of it.

The real strength of an ensemble cast shines through when each actor brings their own gifts and value and exhibits them in ways that only add to the larger value of the production. We see Amara Granderson (Lady in Orange), Tendayi Kuumba (Lady in Brown), Kenita R. Miller (Lady in Red), Okwui Okpokwasili (Lady in Green), Stacey Sargeant (Lady In Blue), Alexandria Wailes (Lady in Purple), and D. Woods (Lady in Yellow)—all in their glory but not in a way that competes for attention.

The play doesn’t pit their stories or talents against one another. Instead, it gives each of them the power to demand attention equally and equivocally—aided by Myung Hee Cho’s scene designs, Sarafina Bush’s costumes, and Jiyoun Chang’s lighting. Even when the pace of the play falters a bit as the narrative builds itself for the very emotionally charged ending, the music and movement of the seven women come swooping in, elevating the narrative in one collective stride.

Shange expressed “I write for young girls of color, for girls who don’t even exist yet,” and for colored girls is a celebration of that triumph—the foresight of a Black woman to create something that speaks to the future and the present. May we never again have to wait 65 years to see that happen; may more colored girls create for more colored girls. As one of the ladies says, “Let her be born and handled warmly.”

Keep Reading

‘How I Learned To Drive’ is a Nuanced Exploration of Memory

As the adage goes, “More Vogel, less Mamet.” Right now on Broadway, this is just beginning to come true, or at least approaching it. Although we have to suffer through both David Mamet’s problematic and dangerous rant about male teachers being pedophiles and a lackluster revival of American Buffalo, we also are graced–thank God–with a […]

Read More

In ‘American Buffalo’ Nostalgia Gets in the Way of Progress

Somewhere in America older men impart wisdom to the younger between puffs of smoke and swigs of Coke. Somewhere in America, life is a powder keg with a short fuse, and morality is but an afterthought, as is breakfast. Somewhere in America, everything hinges on a coin. At the center of American Buffalo, David Mamet’s […]

Read More