The “Hangmen” Martin McDonagh Wrote Lack Accountability, but Should the Play Get Away with the Same?

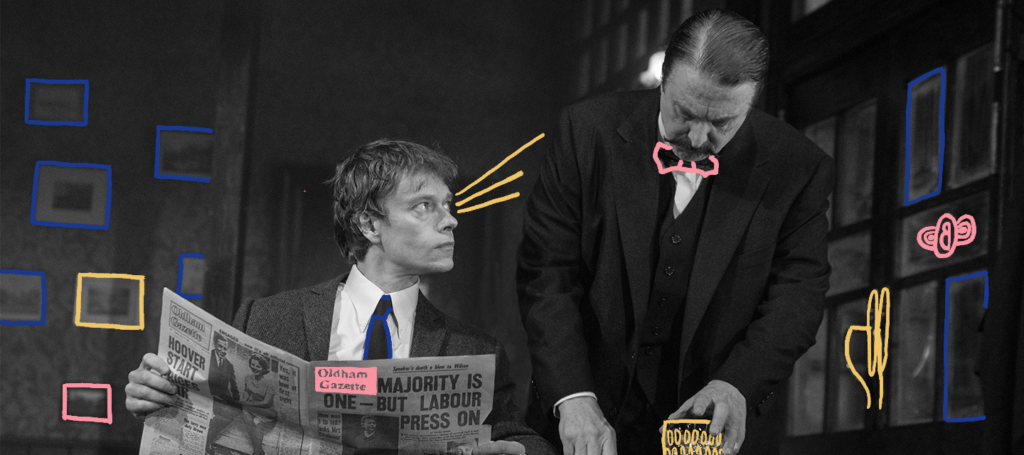

Hangmen, by Martin McDonagh and directed by Matthew Dunster begins on the day the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act was passed in England in 1965. Harry (David Threlfall), a former hangman who runs a pub in Northern England, is suddenly sought after by the press who want to know his thoughts on the historic event. What they, and we, get is a taste of Harry’s nostalgia for his days on the gallows and also of his propensity to take the law into his hands—quickly and short-sightedly.

In true McDonagh style, things start to unravel once a young woman goes missing and the threat of sexual abuse looms large—like Angela in McDonagh’s 2017 feature film, Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. In Hangmen it’s Harry’s daughter Shirley (Gaby French) who goes missing. Harry and his former colleague Syd (Andy Nyman) think the new menacing Londoner in town—Mooney (Alfie Allen)—has something to do with it and they, unflinchingly, take the law into their hands in their pursuit to punish him.

McDonagh’s writing—though aided by some fantastic scenic design by Anna Fleischle and excellent work by stage manager Scott Taylor Rollison and their team—fails to establish Mooney as a character who attracts the audience’s attention or intrigue, as is usual in thrillers. Beyond word plays on his creepiness, menacing nature, and (not) funny temperament, we don’t quite know the how, why, and what of his role in the play, other than to sometimes induce laughs by making jokes that uncomfortably border on racism and homophobia.

We get it, it’s 1965 and people often referred to cigarettes using a homophobic slur, but I wonder, what is the point of making someone say it out loud in 2022? Setting problematic language in a nostalgic past is often an easy way out of facing scrutiny in the immediate context of a production. It is a somewhat time-tested way of evading accountable storytelling.

The play has multiple instances in which Africans are compared to monkeys, which begs the question—what is it that Hangmen and its people are nostalgic for? A world where people (often innocent people) could be hanged so others could tell themselves they’re safe? A world where white people can sit in a bar, say all sorts of racist stuff and call it banter? Within a cultural ecosystem that is trying to reckon with recent social uprisings, and be present and accountable in the way it produces art, what role does a show like Hangmen play and what does it hark back to? What is the nostalgia it is trying to invoke? At a time when debates around defunding the police and concerns over police ineptitude are so ripe, why should I—an immigrant of color—even try sympathizing with someone who is a stand-in for the State

Within the first few minutes of the play, a suspected killer, Hennesy (Josh Goulding) is being prepared for his execution. Drawing on some old-school, accent-driven humor, he remarks that he can’t understand a word of Harry’s Geordie-accented English. All characters in the play—except Mooney—speak in this accent, in varying levels of thickness. Sometimes so fast that the point is to perhaps evade audience comprehension. As someone who is not a native English speaker, I caught myself wishing for subtitles, especially while Shirley delivered her lines pushing back against the “moody”, “sulky” stereotypes her parents confine her character to. I wonder if non-white actors could speak with such thick accents—put on or otherwise—and yet be so well-received by an audience teetering away at extremely rudimentary sexual gags and double entendres.

Who gets to have an accent on Broadway and get away without being subtitled, with an assumption that people will get it anyway? As a South Asian woman, plagued with the legacy of Apu, I wonder what it is about the way my father and uncles speak that can be made fun of but never laughed with.

There is an inherent cruelty in most of McDonagh’s work which he aestheticizes with women always at the receiving end. It’s women who live through immediate physical danger and the ones whose lives stand affected by a passive living out of the violence exercised by men. Both Alice (Tracie Bennett; I really wish there was more of her in the play)—Harry’s wife—and Shirley are props in a narrative where men just wrestle out a power struggle from the intersections of policing, State, and patriarchy. Unlike Mildred Hayes (Frances McDormand in Three Billboards) who goes to the other extreme and makes the character flirt with the limits of legality, the women McDonagh wrote in Hangmen are essentially only reacting to the actions of the men around them, with very little agency.

With its tired jokes and dated humor, Hangmen provides an easy laugh, but it’s a difficult watch for those of us trying to be better audiences; questioning and interrogating works of culture that don’t quite sit right with our conversations around contemporary politics.

Keep Reading

‘for colored girls’ Is a Timeless Movement in Compassion

After playwright Ntozake Shange’s death in 2018, her sister—the playwright Ifa Bayeza—said, “I don’t think there’s a day on the planet when there’s not a young woman who discovers herself through the words of my sister.” As I watched the revival of Shange’s “choreopoem” for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow […]

Read More

‘How I Learned To Drive’ is a Nuanced Exploration of Memory

As the adage goes, “More Vogel, less Mamet.” Right now on Broadway, this is just beginning to come true, or at least approaching it. Although we have to suffer through both David Mamet’s problematic and dangerous rant about male teachers being pedophiles and a lackluster revival of American Buffalo, we also are graced–thank God–with a […]

Read More