This ‘1776’ Forgets the Very People It’s Claiming to Serve

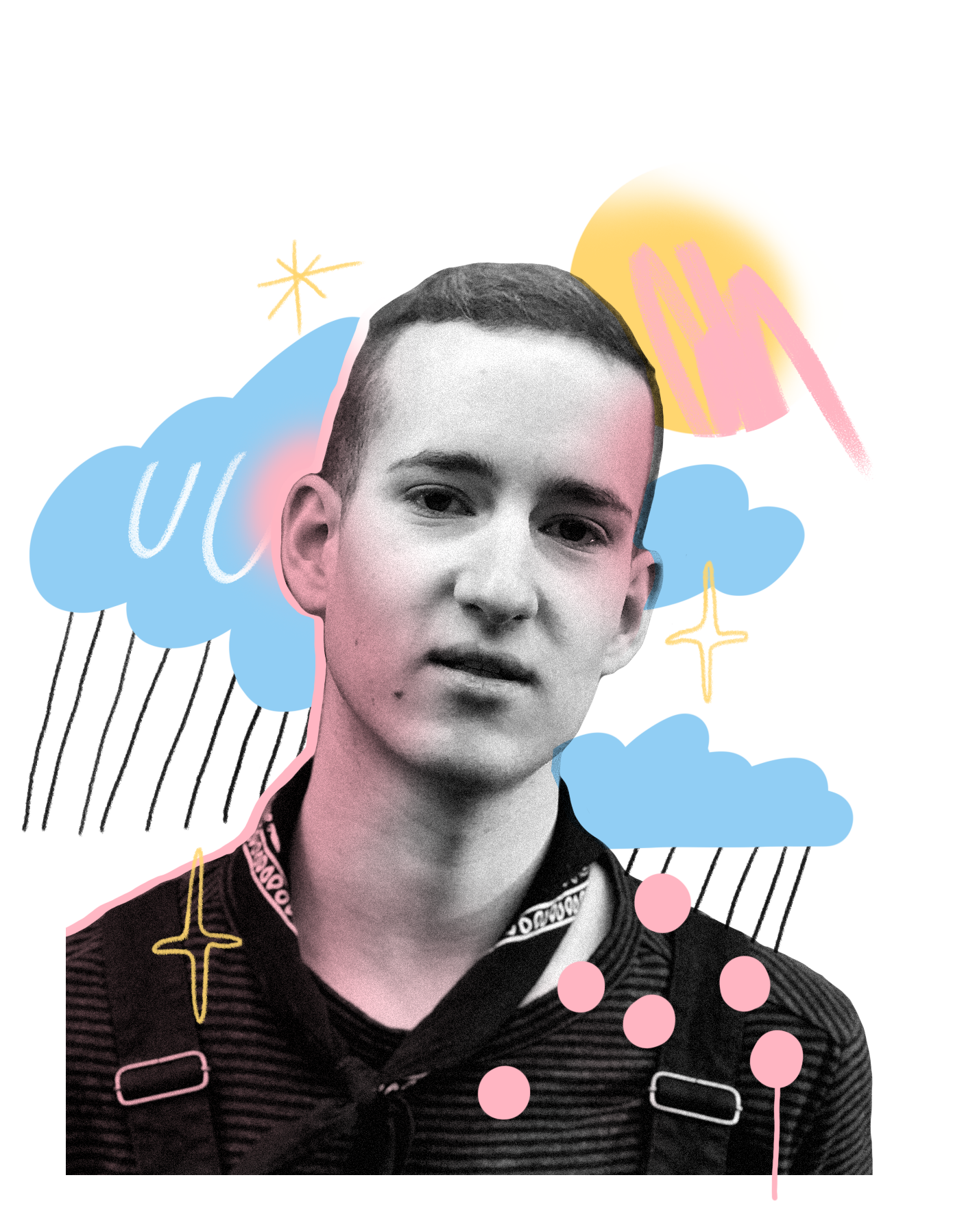

The revival of 1776 – a musical about the all-male, all-white Founding Fathers signing the Declaration of Independence – which opens tonight at the American Airlines Theatre, begins with several women, trans, and nonbinary actors of various races and body types entering the stage in modern dress and putting on historical costumes. Among them is Sav Souza, a nonbinary transmasc actor in a black mesh shirt, with their top surgery scars visible. As a nonbinary trans person sitting in the audience, I almost teared up seeing them; I never have, and didn’t know if I ever would, see someone like Souza on a Broadway stage.

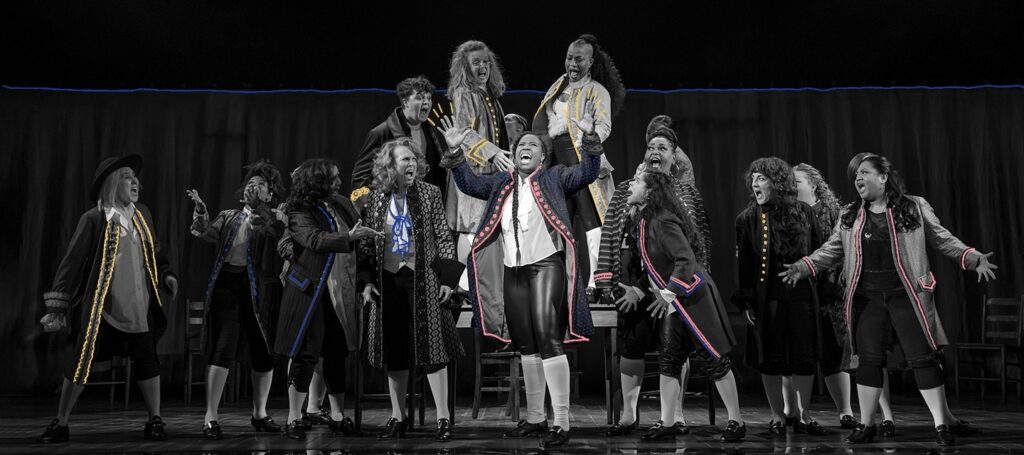

The musical, with lyrics and music by Sherman Edwards and a book by Peter Stone, is usually done as a John Adams-centric show (played here by Crystal Lucas-Perry), but this revival treats it as an ensemble piece, letting several performers—like Patrena Murray (Benjamin Franklin), Shawna Hamic (Richard Henry Lee), Carolee Carmello (John Dickinson), Liz Mikel (John Hancock, the standout performance of the cast), and a deeply pregnant Elizabeth A. Davis (Thomas Jefferson)—have shining moments.

The diversity of this cast is astonishing and worthy of celebration. I am overjoyed that these performers are getting paid, getting work, and getting to be on Broadway, many of them for the first time. I hope to see many more ensembles like this in the future.

Having said that, beyond the cast, there was little I was able to enjoy in this production.

Though there is certainly a great deal of wit in 1776, much of which made me chuckle, there is also quite a bit that made me cringe or left me confused. The musical showcases how ridiculous these “Founding Fathers” were, with their petty debates, complaints, and questionable values (encapsulated best in “Piddle, Twiddle, and Resolve” and a hilarious string of sub-committees), so having a non-male cast adds another degree of poking-fun.

Take for example Adams’s opening line, “I have come to the conclusion that one useless man is called a disgrace—that two are called a law firm—and that three or more become a Congress.” This gets a loud chuckle from the audience, as it should. But beyond showing that these men are clowns, what exactly is the purpose of this casting? What does it mean to have this racially diverse, non-male cast playing all these white men? What does this revival have to actually say about gender?

This semester, I taught the Declaration of Independence alongside other political documents from the period written by women, people of color, and formerly enslaved people. To my CUNY students–the majority of whom are BIPOC–my reasoning behind this was crystal clear. They unanimously expressed frustration with the Declaration of Independence, noting how they are not mentioned or included, and how this document proves that historically this country has not cared about women and people of color. My students preferred all of the other documents, particularly the explicitly feminist ones. Most critically, they noted the horrible hypocrisy of the Declaration of Independence being signed while the slave trade was booming. “All men are created equal,” except not really.

So why do a revival of 1776? Why continue to glorify this document and this group of men? Though the musical exposes them as more of a circus than a caucus, the very existence of this musical is still giving them stage time, literally. Why not create something new? Tell a new story that needs to be heard, a forgotten history.

This made me think of two musicals: Hamilton, whose approach to telling the Founding Fathers’ story with a racially diverse cast (but mostly without racial commentary) seems copied and pasted here, and Suffs, which features an all-female, trans, and nonbinary cast and tells the story of the women’s suffrage movement. Everything this revival is trying to do, in terms of getting its audience to think about gender and complex historical legacies, Suffs does, and does better. Crucially, Suffs is by a woman and is actually telling women’s roles in shaping history.

On the other hand, 1776 focuses exclusively on men’s history, and worse, it’s full of historical inaccuracies large and small: mischaracterizations, altered timelines or geographies, and entire errors in politics and events (most notably, the walkout over slavery in Act II did not actually occur historically). This revival does add Abigail Adams’s (Allyson Kaye Daniel, a standout) famous “remember the ladies” letter, but to no purpose. What should have been a cornerstone of a revival about gender, a true thesis statement moment for co-directors Diane Paulus and Jeffrey L. Paige, is tossed off in a romantic letter exchange song. Nothing is made of the fact that Abigail begs her husband to “remember the ladies” and he completely ignores her. There is something ironically symbolic here since this production also notes that we should “remember the ladies” but then seemingly forgets them, having nothing to say about gender other than restating the mere fact it exists.

Paulus and Page save all their directorial arguments for Act II, articulating them mostly through songs. The first, “Cool, Cool Considerate Men” is a conservative manifesto sung by Carolee Carmello—“ever to the right, never to the left,” we get it. Next is “Momma, Look Sharp,” which seems like the directors’ cri de coeur; they turn the war song into an anthem about women, particularly Black mothers, having to say goodbye to their sons who they watch get murdered. It’s moving, though retrofitted. (In moving “Mamma, Look Sharp” to Act II, the first act ends with “He Plays the Violin,” perhaps the most pointless and confusing Act I finale I’ve ever seen.)

After this, in a particularly egregious sequence, the Declaration of Independence gets read while a video montage (projection design by David Bengali) of various key moments in US political history—women’s suffrage, civil rights, the legalization of same-sex marriage, etc.—is projected on a curtain. The production thus makes a direct throughline from the Declaration of Independence to all those other human rights victories won by women, people of color, queer people, and trans people, heavily implying that they would not be possible if not for the work begun by the Founding Fathers.

I found this morally reprehensible and difficult to watch. I was upset by the applause it garnered. It felt like propaganda, and it’s a lie. To give just one example: if the United States had remained colonies, slavery would have been abolished in 1833 (as it was in all British colonies), instead, because of the Declaration of Independence, America held on to slavery for an additional thirty years.

In “Molasses to Rum,” Edward Rutledge (Sara Porkalob) belts a fiery defense of slavery and points out New England’s dependency on it, even if they purport to oppose it. The song is choreographed by Page to include a slave auction, and in Scott Pask’s only major set change in the production, a curtain reveals a wall of barrels, a chilling symbol for the byproducts of the triangle slave trade. While the song, and all its terrors, highlights the dark history of white supremacy at the core of this country, the staging is quite troubling and brings up a host of issues.

The song is performed by Porkalob, thereby making an Asian woman the mouthpiece for American slavery. The dancers in the slave auction are the majority of the Black actors, who symbolically remove their 18th-century coats to let us know they are no longer their characters (a dramatic rule established throughout).

However, once the song is over, they don their coats and go back to their roles, some of them as pro-slavery delegates; Mikel goes back to playing John Hancock, and immediately asks for a mug of rum, even after the song just mentioned that it comes from slavery. It was uncomfortable and jarring to see these Black actors go from dancing as slaves to playing characters either pro-slavery or complicit with it.

This led me to wonder: how does this production’s focus on gender align with its focus on race and slavery? How do they work together? Do they work together? It was white men primarily who kept slavery legal, and yet in this production, a group of diverse (including many Black) women, trans, and nonbinary people play those roles. The production often wants to ignore gender and race, and have us suspend disbelief as we watch this cast play white men, while sometimes bringing our attention to the gendered and racialized bodies of the performers. It wants to have it both ways, offering a messy, muddled message.

The ending best encapsulates my own deeply mixed feelings. As the Declaration gets signed, the signatures of each man are projected onto a wall, which slides away to reveal, once again, the looming wall of barrels. In a chilling, eerie, and evocative moment, several signatures get projected directly onto the barrels, arguing that these men co-signed not just American independence, but American slavery.

Immediately after this, three cast members enter and sing a reprise of the lyric “does anybody care?” It is not just any three cast members, though: it’s Souza, Sushma Saha, and Brooke Simpson—a nonbinary transmasc actor, an Asian actor, and an Indigenous actor. They’re not in their costumes, they’re performing as themselves, so it’s hard to interpret their being featured here as anything other than tokenism. From here, the rest of the cast enters, holding their 18th-century jackets out, and a spotlight rests on Lucas-Perry.

Is this an indictment of the Founding Fathers (specifically Adams?) and their complicity in slavery? A good point to make for sure, but an odd one to end on, since this musical, while containing a discussion of slavery, is not primarily about slavery; this felt untrue to the 2 hours and 40-minute musical I had just watched.

So what am I to make of this production? It felt hollow, unsure of what it was trying to say, and rife with identity-based issues–but it also features a groundbreakingly diverse cast, which I enthusiastically applaud. I can only hope that their next projects are more politically sound.

While I began the show so happy to see Souza, when it ended I was upset with how they were being used as a token. I just cannot get behind this revival’s attempt at giving a new facade to a rotting building. Maybe this production says something after all, albeit unintentionally: much like America, this 1776 revival takes one step forward, several steps back.

Keep Reading

The Gorgeous ‘Cost of Living’ Depicts Disability in Groundbreaking Ways

Last season, Martyna Majok stunned audiences with her gripping portrayal of immigrant life in Sanctuary City; now her earlier play, Cost of Living, which won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2018, is making its Broadway debut–as is the playwright. Last year I extolled her work as “off-Broadway at its best,” and this year I […]

Read More

Loss and Remembrance are at the Heart of the Magnificent ‘Leopoldstadt’

Everything in Leopoldstadt unfolds like a game of cat’s cradle. It’s 1899 and the Merz & Jakobovicz family portrait is one of abundance and contentment. The conversations flow along with whiskey and music, as family members discuss Freud’s latest theories, which Hermann Merz (David Krumholtz) disdains, mathematician Riemann’s still unsolved hypothesis, which Ludwig Jakobovicz (Brandon […]

Read More